[Personal] Error budgeting: understanding your issues is the first step to solve them.

Table of Contents

Here is the first real post about quantum error-correction! Let’s talk about some work I have recently done on error budgeting, why it is interesting, how it works, and what was needed to make it work.

What is error-budgeting?

Before defining error-budgeting, let me (re-)introduce a few important metrics of quantum error correction.

The logical error probability

One of the most important metric in quantum error-correction is the logical error probability. It is the probability of having an error, even with the error-correction protocol. This is a core quantity in quantum error-correction as it dictates how many gates you can probably execute reliably before seeing errors.

But the logical error-probability has one problem as a metric: it depends on too many parameters! In particular, it depends on the computation you are considering. Surely, the logical error-probability of running an end-to-end implementation of Shor’s algorithm (or improvements of it) is not the same as the logical error-rate of keeping you quantum information alive for a short period of time (also known as a “memory experiment”).

$\varepsilon$: the logical error probability per round

To improve the metric, researchers came up with the logical error-probability per round, often written $\varepsilon_d$ for the distance $d$. Most quantum error-correction codes implemented in practice at the moment need to repeat the same operation (a “round”) several times to ensure that errors are correctly accounted for by the decoder.

This metric is way better, as it can now be assumed computation-independent. Using the same hardware, with the same code implementation and the same distance, the logical error probability per round for an implementation of Shor’s algorithm and for the simplest possible memory experiment should be the same.

But can we do even better and have a distance-independent metric?

$\Lambda$: the error suppression factor

It turns out we can, and this new metric is called $\Lambda$. It is the multiplicative factor by which the error probability per round is reduced when you increase the fault-distance by 2 (or equivalently, when you can correct one more physical error). In mathematical terms:

$$\Lambda = \frac{\varepsilon_{d+2}}{\varepsilon_d}.$$

This metric only depends on the code being implemented, its practical implementation, and of course the hardware error-rates.

In particular that means that, for a given hardware, you can compare the efficiency of different error-correction code implementation by comparing the value of $\Lambda$ they reach.

OK, but where is the budget?

What’s a “budget” in the first place? A budget is defined by a quantity that you want to minimise and that can be written as a sum of independent contributions.

In our case, we want to minimise $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ (because that is equivalent to maximising $\Lambda$).

The only problem left is “how do we meaningfully split $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ into contributions from different sources?”. This has been answered by the research paper “Exponential suppression of bit or phase errors with cyclic error correction” in Appendix C where the authors justify that $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ should be approximately linear in each error-rate corresponding to physical error mechanisms.

That means that $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ can be approximated as a sum of contributions that scale with each error-rate (e.g., $2$-qubit gate error-rate, idling error-rate, …).

And here is our budget: $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$! Error-budgeting then amounts at computing the different contributions to $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$.

An error-budget? What for?

Let me cite myself for a moment:

Before even thinking about modifying code to optimise, a crucial thing should be clear in your head:

BENCHMARK IT

Sadly, the system I use to write this post (wowchemy, amazing work) does not allow me to emphasize this even more: BENCHMARK, BENCHMARK and BENCHMARK.

Without benchmark, you cannot know for sure what part of your implementation is slow. You may guess, and you may guess right, but you will not know for sure until you implemented the optimisation and saw the results. Benchmarking allows you to have a certainty about the problematic parts of your code.

I said that more than 5 years ago, I stand by it, and will still stand by it in 50 years.

With quantum error-correction, we want to minimise $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ to make our error-correction more efficient. The only way to guide the optimisation process towards minimising $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ is to have an error budget (i.e., benchmark) that shows you what you should focus on improving.

Computing an error-budget

There are two main ways of computing an error-budget, and they both involve computing the gradient of $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ (denoted $\nabla\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ later) with respect to the error-rate of each error mechanism.

The two main ways differ on the point at which the gradient should be computed. Using $\vec{p}$ to represent the error-rates calibrated on the hardware of interest (i.e., parameters of your noise model), the gradient should be computed at:

- $\vec{p}$ when using a first-order approximation for $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$,

- $\frac{\vec{p}}{2}$ when using a second-order approximation for $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$.

The implications of using one method over the other would be too much for this blog post, but might be a good target for another blog post!

The problem of “computing an error budget” now becomes “computing the gradient of a noisy function”.

Wait, you wrote “noisy”?

Yes. The chain to compute $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ is the following:

- $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ requires to compute $\Lambda$,

- $\Lambda$ requires to compute $\varepsilon_d$ for at least 2 values of $d$,

- $\varepsilon_d$ requires to compute the logical error probability for different numbers of rounds,

- the logical error probability estimation relies on Monte-Carlo sampling (often with

stim).

Monte-Carlo sampling returning an estimate with a given uncertainty, that uncertainty is propagated up to the estimation of $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$, and so the values we can compute for the function $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ inherently suffer from uncertainty (i.e., noise).

There are several ways to approximate numerically the gradient of a function. Most of them rely on numerical methods that do not cope well with noisy values, the prime example being the standard finite differences formulas.

But using multiple values of $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ evaluated at different noise strengths, it is possible to approximate $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ with a polynomial of degree $d$ and then compute the gradient of that polynomial at the point of interest. This method allows to:

- reduce the numerical sensibility to the uncertainties in $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ of the gradient estimation procedure,

- allow to compute the standard deviation of the gradient estimation.

Analysing an error-budget

Now comes the interesting part where you can use error-budgeting to understand your hardware better and find ways to improve your error-correction!

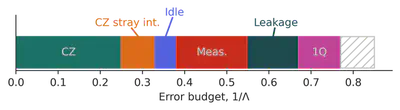

Let’s say that you estimated the error-budget of your implementation of the rotated surface code on a specific hardware with several noise sources and obtain the following budget:

This image encapsulates a lot of information about your actual error-correction performance and how to improve it.

The right-most area dashed in white represents the “Excess” noise, which is the difference between the value of $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ computed on the real hardware error-model ($\approx 0.85$ by reading the plot) and the value obtained by combining each individual contributions.

The $2$-qubit error-rates account for $\approx 0.32$ of the total budget, which is $\frac{0.32}{0.85}\approx 38\%$ of the total budget. That means that dividing your $2$-qubit error-rate by $2$ would reduce your $\frac{1}{\Lambda}$ by $\approx 38 / 2 = 19\%$ and so increase your $\Lambda$ by $\approx 23\%$.

Reducing the idle noise would probably not have a large impact on your error-correction performance because idling noise is only $\approx 6\%$ of the budget.

Conclusion

I would argue that trying to improve your error-correction performance without error-budgeting is like trying to find a neddle in a haystack while being blindfolded: you can try, but that’s probably not the most efficient way of doing it.

So use the new error-budgeting capabilities of deltakit ADD LINK TO DOCUMENTATION HERE, tailor your noise models to your hardware, and let’s improve these logical error probabilities!